Films

Listening with vision

An essay on Thu Van Tran's films by Pedro Moraïs, 2019

« La mémoire est notre médium et nous vivons dans la matière », dit Thu Van Tran, affirmant le caractère construit de la mémoire, toujours incomplète, sujette à être manipulable, mais aussi en capacité d’être élargie à des points de vue longtemps minorisés, et alors modifiable et impermanente. Mais c’est sans doute la seconde partie de son affirmation qui apparaît comme sa signature : si son travail intègre la narration, le récit, l’analyse critique de l’histoire et son parcours de vie personnel, c’est à travers la matière que Thu Van Tran construit sa pensée.

D’une certaine manière, malgré une conscience critique vis-à-vis de l’autonomie de l’oeuvre moderniste, elle travaille là, dans ce rapport aux matériaux, en prise avec une dimension irréductible à l’art. Pourtant, avant même de parler d’art, cette attention à la matière s’inscrit dans une optique plus large, celle qui met son travail en lien avec notre vie matérielle : les sensations déclenchées par le toucher et la lumière, la biographie des objets dans leur relation à l’empreinte des gestes et à la forme même du corps, l’économie et le lien au travail qui organise et sous-tend notre environnement le plus proche.

Son geste artistique inaugural – l’affirmation « La Jaune parle » – énonce précisément sa position singulière, entre importance accordée à la picturalité et au langage et le retournement d’une assignation identitaire. Dans cette phrase, on devine aussi le long silence qui la précède. L’ensemble du travail de l’artiste apparaît dès lors comme un long chemin pour conquérir le langage et s’en défaire. Cela peut prendre la forme d’une traduction ou d’une transmission orale, mais la question essentielle reste la même : dans quelle langue parle-t-on ? Ce dialogue ne pourra se faire qu’à travers une écoute au présent des sédimentations de la mémoire d’un pays. Son travail filmique traduit cela dans sa forme même, employant des moyens digitaux mais aussi analogiques dont elle gardera les effets de solarisation, des éclairs de lumière nous renvoyant à une archéologie des moyens d’enregistrement du réel.

Les regards caméra dans les films de Thu Van Tran semblent dialoguer avec un ecosystème temporel organique et minéral. Un moment suspendu dans lequel se dessine une vision du monde où l’humain, l’animal, le végétal et le minéral sont imbriqués et interdépendants, dans la continuité de la réflexion des anthropologues Philippe Descola ou Eduardo Viveiros de Castro. Selon eux, la nature n’est pas ce qui entoure l’humain : il n’y a pas de nature indissociable de la culture, mais un écosystème de relations qui nous oblige à décentrer l’humain et à refuser la hiérarchie du vivant et du non-vivant.

Dans chaque film de Thu Van Tran, cette vision du monde est manifeste : tout ce qui est filmé apparaît comme appartenant à un écosystème. La nature n’est pas un espace idéalisé mais une composante de nous-mêmes, et le travail de l’artiste est toujours celui d’une vision à l’écoute, de ce que peut nous apprendre une langue que nous ne connaissons pas, qu’elle soit humaine, animale, végétale ou minérale. Ce travail n’ évacue pas une lecture politique de l’action humaine. Quand elle filme les cicatrices sur l’écorce des hévéas – un geste que la machine ne parvient pas à remplacer –, cette entaille renvoie immédiatement à son travail précis et incisif sur l’histoire politique du Vietnam et l’exploration coloniale du caoutchouc. Quand elle filme à Hong Kong des femmes liées au travail dit domestique en train de se réunir dans l’espace public, cette manifestation n’est autre que le besoin d’exister, une revendication silencieuse des corps invisibilisés qui s’établit dans l’ échange et la complicité.

Thu Van Tran ancre sa lecture des mécanismes qui colonisent les corps, les arbres ou le langage dans une subtile traduction à travers des indices, des matières, des associations d’images. La perception de la violence coloniale traverse ses films et cohabite avec le spectre élargi des sensations du monde : « il y a des gestes d’émancipation en parallèle avec des gestes colonisés, des gestes de récolte et des gestes de révolte ». Nous sommes pris dans les discordes héritées dans les paradoxes passés, est-il dit dans un passage de « 24 heures à Hanoï ».

Sans doute l’un des plus difficiles paradoxes à résoudre pour ceux qui ont connu l’exil, en lien avec ceux qui ont connu la colonisation, est d’avoir à retrouver une identité tout en sachant que celle-ci ne peut être que construite. Est-ce qu’une identité se constitue ainsi, dans sa confrontation aux rapports de domination ? Est-ce ce qui la conditionne qui la fait exister ? « Les arbres du caoutchouc sont tels des parasites, ils ont besoin d’un hôte et se greffent sur un arbre fruitier, déjà enraciné », évoque Thu Van Tran, qui semble affirmer tout au long de son travail, en faisant appel au corps, aux sens, à l’écosystème des relations de l’humain et du non-humain, qu’une identité ne suffit pas pour saisir la complexité de l’exil.

“Memory is our medium and we live within its fabric,” says Thu Van Tran, affirming the constructed character of memory, which is always incomplete, prone to manipulation, but also capable of expanding to encompass points of view that have long been excluded, and is thus modifiable and impermanent. But it is undoubtedly the latter part of her affirmation that emerges here as her signature: while her work integrates narrative, story, critical analysis of history, and her own personal background, it is through materials that Thu Van Tran constructs her thought.

In some sense, despite a critical awareness with respect to the autonomy of the modernist oeuvre, she works in this arena, in this relationship to materials, by grappling with an irreducible dimension of art. However, even before speaking of art, this attention to materials pertains to a wider purview, relating her work to our material life: the sensations triggered by touch and light, the biography of objects in their relationship to the traces of gestures and the very form of the body; the economy; and the association with labour, which organises and underpins our immediate environment

Her inaugural artistic gesture – the affirmation “yellow speaks” – precisely enunciates her singular position, between the importance accorded to pictoriality and the language and reversal of a given identity-allocation. In this phrase, we also get an inkling of the long silence that has preceded it. The artist’s entire oeuvre thus emerges as a long road travelled in order to conquer and rid herself of language. This may take the form of a translation or an oral transmission, but the essential question remains the same: which language are we speaking in? This dialogue could only emerge by listening in the present to the sedimentations of countries’ memory. Her film work expresses this in its very form, using digital but also analog means, whose solarisation she retains, flashes of light that point to an archaeology of the means of recording reality.

Camera looks, in Thu Van Tran’s films, seem to be dialoguing with an organic and mineral temporal ecosystem. A suspended moment in which a vision of the world is adumbrated and where emerge human, animal, plant, and mineral that are imbricated and interdependent, in keeping with the thinking of anthropologists such as Philippe Descola or Viveiros de Castro. According to these theorists, nature is not what surrounds humanity: there is no nature inseparable from culture, but an ecosystem of relationships that oblige us to decentre humanity and reject the hierarchy between the living and the non-living.

In all of Thu Van Tran’s films this worldview is manifest; everything that is filmed is presented as belonging to an ecosystem. Nature is not an idealised space, but a component of ourselves and the artist’s task is always that of listening through vision, to everything that might teach us a language we’re unfamiliar with, whether it be human, animal, plant, or mineral. This work does not divest human action of a political reading. When she films the scars on the bark of rubber trees – a gesture that machine are unable to replace – this cut immediately relates to her precise and incisive work on the political history of Vietnam and the colonial exploration of rubber. When she films women in Hong Kong involved in “domestic work” meeting in public space, this event is none other than the need to exist, a silent affirmation of bodies rendered invisible, which is established through discussions and affinities.

Thu Van Tran firmly roots her interpretation of the mechanisms that colonise bodies, trees, or language in subtle expressions – through clues, materials, and image associations. The perception of colonial violence pervades her films and coexists with the wider spectrum of global sensations: “there are gestures of emancipation alongside colonised gestures, gestures of harvesting and gestures of revolt”. We are caught up in the discords resulting from past paradoxes, a passage in “24 Hours in Hanoi” states.

Doubtless one of the most difficult paradoxes to resolve for those who have experienced exile, akin to those who have experienced colonisation, is that of having to recover an identity in the knowledge that this can only be a constructed one. Is identity therefore constructed in its confrontation with power relations? Is that the condition that allows its existence? “Rubber trees are like parasites, they need a host and graft themselves onto a fruit tree that has already taken root,” evokes Thu Van Tran, who seems to affirm throughout her work, by calling on the body, on the senses, and on the ecosystem of human/non-human relations, that an identity is not enough to grasp the complexity of exile.

24 hours in Hanoï

28’53’’ - Double screen film projection - Sound - 2019

16mm film transferred in video color 2K.

Ecktachrome film roll 250D, negative 50D and 200T Kodak. Subtitles.

“24 hours à Hanoï follows a woman as she meanders through a city she does not know, during the time span of one rotation of the Earth, divided equally between one day and one night. This cycle leads to a succession of revelations to which Hoa Mi responds mutely: the silence of contemplation, and that of the outsider. Innocent and kind, she is a sort of lost Candide, except for what she’s doing: retracing a family history long kept buried. Hoa Mi the lock picker.

The past is sometimes unable to intercede in the present. But on the contrary, in Hanoi, time’s circle seems to have been distorted into an imperfect curve, like the country’s sinuous and humid geography. Past and present confront each other in a ceaseless, futile tug of war. No future emerges on the horizon. Dreaming or awake? These twenty-four hours are a theater of apparitions, souls who will revisit our present existence, turtles who will recite poems while we remain prisoners of the discord of a country now transfixed by the paradoxes of its past.

This dead end, closed off centuries before to the history of Vietnam at the moment when it lost its original language—can the enchanted eyes of an outsider finally find a way out?”

— Excerpt from the narration of the film 24 hours in Hanoï.

Si rien ne sort d’ici

If nothing comes out from this

08’07’’- Silent - 2018

16 mm film. Negative film roll Kodak 50D and 200T. Transfered images from iPhone,

5DRS drone.

The film is separated into what the artist calls four ‘breaths’, and focuses on four gestures and thoughts. Scene one shows plaster casts being broken, revealing letters of the alphabet that compose the phrase Si rien ne sort d’ici. This is a symbolic gesture that refers to the birth of language. Scene two shows a group of female Filipino domestic workers in Hong Kong who gather in public space on Sundays, as if in silent protest. Scene three depicts a volcanic eruption, a telluric force that haunts the artist, as does the overbearing humidity of the tropical forests. The last scene returns to the motif of the rainbow in a moment of beauty and redemption. The succession of gestures and images infers different ‘liberations’ of sorts. The title, Si rien ne sort d’ici, is a phrase that, for the artist, is a call to utterance, to expression and, finally, to an emancipation of the self.

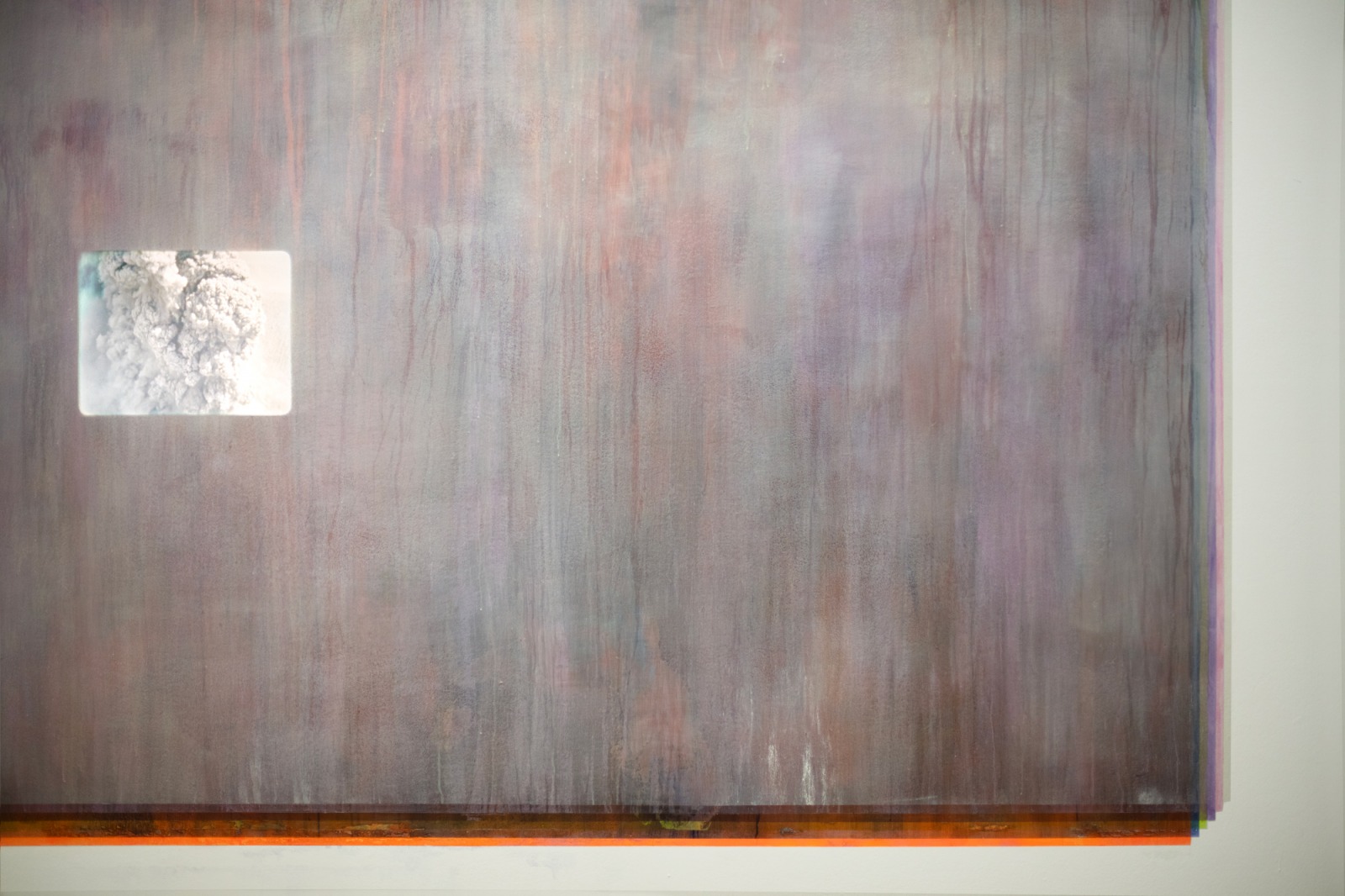

The film was projected, for the Prix Marcel Duchamp at Centre Pompidou, on a fresco, a large site-specific wall paintings, Colours of Grey, which dominate the space, as an expansive grey field. The paintings, non-pictorial and achromatic, create a contemplative, almost sacred space. Yet this pared-down space and abstraction is deceptive, revealing different layers of materiality, image and meaning. The work is, in fact, a continuation of Tran’s longterm investigation into the semantics of colour: the grey is produced by mixing six different colours that gave their name to the defoliants used by the US military during the Vietnam War (agent orange, purple, blue, green, pink, white).

This grey field serves as the material and conceptual backdrop for the film Si rien ne sort d’ici.

— Excerpt from the text On Stains, Traces and Silent Witnesses, by Katerina Gregos, catalog of The Marcel Duchamp Prize, Pompidou, 2018.

The Yellow speaks

Or a short narrative on the surface of the glory of the French colonial expansion.

04'12" - Sound - 2017

Negative film roll Kodak 50D and positive Wittner black and white transfered in digital, included subtitles.

The Yellow Speaks is a film composed of sequences shot on the former places of the colonial exhibition of 1907 which took place in the garden of tropical agronomy of Vincennes city and accompanied by a text written and told by the artist. The title seems to shift between the images we see and the text we hear. Yet both are linked to the artist’s personal history and the colonial history of Indochina, as the subtitle says, “a short story told on the surface of the glory of French colonial expansion”. The statues filmed very closely are a set, made by Jean-Baptiste Belloc in 1913 and called «Monument to the expansion of colonial glory», illustrate each «race» working for the construction of the French Empire. These remains are now stored in an alley of the garden, as if abandoned, hidden from view, since it is now a ruin acting as a reminder of the decline of the colonial empire: the glorious cockerel is missing a foot, fungus is eating away at the face of the Republic and the grey of the stone is overgrown with moss.

A poetic text is superimposed on these images and makes several consciences hear. Like a letter addressed to distant absentees, the story resembles a prosopopoeia, this way of making the absentees speak, as if the statues were delivering their history or their thoughts. Narrated at a rapid pace, making the artist’s breath heard, the short story is interspersed with the memory of the run of a father and his little girl through the jungle, projecting the listener into another memory, alive and closer to us. The statues, although filmed in such a way as to reveal their sensuality, also illustrate, by their petrified and grey bodies, the frozen images of real bodies and the disappearance of colors after the successive wars in Vietnam, a recurring motif in the artist’s work.

— Notes from FRAC Aquitaine collection, written by Magali Nachtergael, 2018.

This excerpt does not incude the sound track of the reader, which should invest the entire projection room with speakers.

Overly forced Gestures (De Récolte à Révolte)

02'21'' - Silent - 2017

Super 8mm film transferred in 16mm

Reversal film roll Kodak ecktachrome 100D and negative 50D.

The artist shows in a film, natives engaged in the extraction of rubber from Hevea tree trunks. She fixes then the features of these mechanical and forced gestures in sculptures.

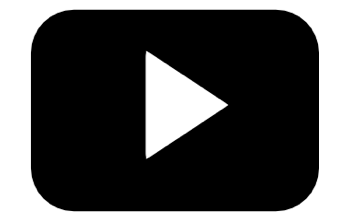

In the first part, we could see people in south Vietnam working in a former French rubber plantation (specially a female worker whose mother had worked in Michelin plantation in 1920’s). The picture focus on their gestures. The same gestures are then, in a second part, petrified into sculpture. In the form of small theatre scenes, some human hands open some molds from where appear other hands fixed in a gesture. The overly forced gestures developped in a context of domination (to harvest), archived in the first projection, are then delivered in a second projection, into sculpture and into the emergence of an independent and new language (to fight).

In the French language there is this almost homonym: de Récolte à Révolte , which could be translated as “from Harvest to Fight’’. This cinematic essay is somehow the materialization of that linguistic statement. And finally, trought the sign language, we can read more actions such as: to be indignant, to gather, to abandon, to build, to destroy, to betray, to milk, to flee. Forced gestures in the path of liberated gestures, an emancipation.

— Excerpt from the catalog of the 57th international exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia - 2017.

Saigneurs

34'48'' - Silent - 2015

Super 8mm film transferred in 16mm

Reversal film roll Kodak ecktachrome 100D.

Born in Vietnam but having grown up in France, Thu-Van Tran challenges one of the major economic links between the two countries during the 20th century, the intensive growing of the para rubber tree, from which rubber is produced. The para rubber tree, for which the first seed was brought from Amazonia by a French sailor, soon became a rich natural resource for Vietnam, but subsequently entailed the occupation of the majority of fertile land by French settlers. The artist screens a film, which relates her travels to the former Michelin plantations in Vietnam, as well as those, which Ford tried to set up, at Fordlândia in Brazil, but failed. This Super 8 film recalls a direct connection, without distance to the filmed subject, but also memories of the not-so-distant past. Tran uses a hidden camera, revealing instants in time, thus creating a metaphor for the syncopated rhythm of memory. The wealth of vegetation is strongly perceptible.

— Excerpt from the press release of the exhibitionThe Red , a solo show by Thu-Van Tran at Rennes 2 University (FR), 2015.

Here an excerpt of the 02'46'' first minutes.

Far East

02'46''- Silent - 2016

Super 8mm film transferred in 16mm

Negative film roll Kodak 50D, reversal ecktachrome 100D.

From Vietnam to Germany, a visual essay proposed as a brief and subjective history of the vestiges of a communism of thought. Shot in Berlin, the film invests, in the first half part, statues such as oracles, almost incantatory which has been set up during GDR; and lingers then in a second part on posters found in China Town. Situated in Lichtenberg, a district of former East Berlin, this China Town consists of alleys of hangars without any window, within which a multitude of shops and Asian restaurants are piled up, and which the only perspective for the people would be, as exits and winsdows to the outside, those posters. An immigration dating from the East block.

— Excerpt from the press release of the exhibition Exchange of presents, a solo show by Thu-Van Tran at n.b.k. (Neue Berliner Kunstverein-DE), 2016.

Our Lights

06'00'' - Silent - 2013

Super 8mm film transferred in 16mm

Reversal film roll Kodak ecktachrome 100D.

Our Lights is a film directed by Thu Van Tran in spring 2013 during a road trip through former Bosnia Herzegovina. Filming in Super 8, Thu Van Tran brings back to life an outdated technology. The intimate nature of this road movie is accentuated when one considers that the artist returned to Sarajevo and filmed places from our recent and common past. The Cyclops, light machine developed by the artist, often appears in shot, and brings into the film a notion of instability or even absurdity (this system does not enable the scene to be lit, it is rather an archetype of a source of light). Symbol of a gaze, the Cyclops illuminated, pointed light towards historical or derisory locations, in a random journey through the landscape of Eastern Europe. It is moved by the artist from site to site and becomes a character in itself, as a constant witness, a spectator of a painful past, a story that is still being reinterpreted even today. The fragility of memory is also evident in the lack of soundtrack which guarantees the artist a degree of detachment. By questioning the uniqueness of perspective through the Cyclops and its unique lighting, she challenges the perception of historical events and the European past, but without falling into cliché or miserabilism.

— Excerpt from Art Basel Statements catalog, 2013.